-----

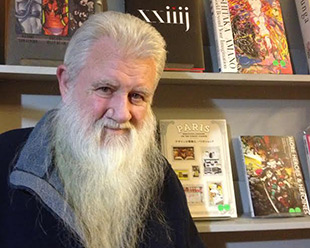

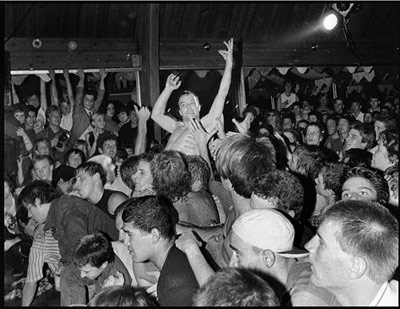

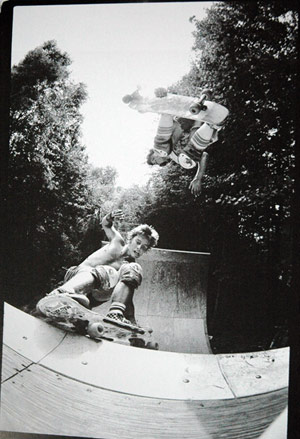

Glen Friedman is showing works from two of his books, Fuck You Heroes and

Fuck You Too, at the 941 Geary Gallery in San Francisco starting tomorrow night, Nov 6th.

These photos have been touring the world for the better part of a decade and half,

and so they’ll be familiar to many of you already. The point of the show, then, may

not be to see these photos for the first time, but to see them again and be reminded

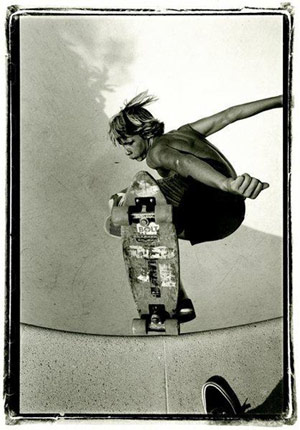

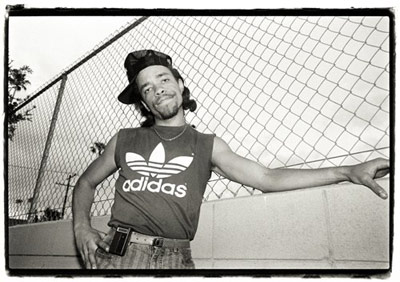

of why they’re so firmly a part of this culture (skateboarding, punk rock, hip hop)

that we love so much. Additionally, we’ll get to see some of Friedman’s

collaborations with Shepard Fairey.

In advance of the opening, this Saturday, November 6th, I spoke with

Friedman over the phone (after an elaborate ritual by which I contacted his

publicist, who then e-mailed Glen my contact information, who then called me from

his blocked number—a level of secrecy and intense concern for privacy I’d never

experienced before [maybe I’ve been interviewing the wrong people so far?]). What I

took away from our talk was part awe at an inarguably legendary photographer (one

whose work I personally admire and find greatly inspiring), and part confoundment

due to Friedman’s lack of humility and his bitter disdain for art he dislikes and for

any criticism of those he holds in high esteem.

In advance of the opening, this Saturday, November 6th, I spoke with

Friedman over the phone (after an elaborate ritual by which I contacted his

publicist, who then e-mailed Glen my contact information, who then called me from

his blocked number—a level of secrecy and intense concern for privacy I’d never

experienced before [maybe I’ve been interviewing the wrong people so far?]). What I

took away from our talk was part awe at an inarguably legendary photographer (one

whose work I personally admire and find greatly inspiring), and part confoundment

due to Friedman’s lack of humility and his bitter disdain for art he dislikes and for

any criticism of those he holds in high esteem.

In short, during our brief chat, Friedman lived up to every expectation I’d held; every anecdote of pompousness seemed to me truer after having spoken to him, but likewise, my appreciation of his doggedness and artistry was also more actual and, in a way, deserved. At the end of it, the idea was only reinforced that there’s no true answer to the question of art vs. artist. Whether or not art can be separate from its creator, we live in a world of copyrighted images and brand names, and our discussion of a work of art takes place within a framework of context and intent. Regarding something and being able to appreciate it based purely on aesthetic grounds is noble and maybe the only true measure of its value as art, but our valuations remain colored by our own biases. But still, but still, Glen Friedman has made some of the most beautiful and important and inspiring images of the past 30 years. They’re even in the Smithsonian.

Anyhow, here’s the first part of the interview. Take from it what you will.

Anyhow, here’s the first part of the interview. Take from it what you will.

GF: There will be two new photos added at the last moment, that I literally took this month, or in October, two photos that I took that I thought were pretty cool, to show people that I’m still doing it sometimes.

GF: They’re just music photos. I have been shooting skating stuff as well, but I didn’t put one of those in the show. I just liked the music stuff. One of the music shots [was] this really young band that I don’t even know what to make of them at this point, but I had a really good time at the show so I shot some photos and I got a picture that I think is my favorite photo of the year, or one of them anyway, so I figured I should put it in the show because it’s so bad ass.

GF: And then I also got a picture of Keith Morris in his new band, OFF! I just went

down to see Keith, I hadn’t seen him in a couple of years, and he’s just a good old

friend, one of my heroes, one of the original Fuck You Heroes, really. And he’s

playing in a new band, and they were playing in a record store just a couple of

blocks from my house, so I went and saw them and brought my camera and took

a couple of photos. I thought it’d be cool to have photos of Keith, singing in a band

in a record store, you know, with vinyl on the walls behind him, and sure enough it

was great. He had the same energy as always, even though he’s over 50 years old it

was great; they were totally good. We’re gonna throw those two new photos in the

show—20 years in between those photos and the other photos in the show. When

the inspiration’s there, the photos come.

GF: And then I also got a picture of Keith Morris in his new band, OFF! I just went

down to see Keith, I hadn’t seen him in a couple of years, and he’s just a good old

friend, one of my heroes, one of the original Fuck You Heroes, really. And he’s

playing in a new band, and they were playing in a record store just a couple of

blocks from my house, so I went and saw them and brought my camera and took

a couple of photos. I thought it’d be cool to have photos of Keith, singing in a band

in a record store, you know, with vinyl on the walls behind him, and sure enough it

was great. He had the same energy as always, even though he’s over 50 years old it

was great; they were totally good. We’re gonna throw those two new photos in the

show—20 years in between those photos and the other photos in the show. When

the inspiration’s there, the photos come.

GF: Well, the goal has always been the same to me. I don’t think really think it’s

progressed that much, to be honest, but I don’t think it’s needed to. I think it is

what it is, and maybe I’ve perfected my mode a bit more, but by about 1991 or

1992 I stopped using a flash altogether for my music stuff, so that’s probably one

of the reasons I don’t shoot it as much.  Also, I just wanted more of a natural light.

The flash would bring so much attention and really distort the whole show. I don’t

want to be part of the whole show, I’m just a person there, and when a flash goes

off it’s bringing attention to that exact moment I’m capturing, which I’m happy to

capture, but I don’t need to be awkward and have a flash and getting it in the way

of everyone else. It kind of makes me think, even when I did shoot the last couple of

weeks, how awkward it was and disgusting it was that there were so many fucking

photographers there, sticking their cameras up in the air, not even looking through

the lens trying to get a photo. It was kind of an unfortunate circumstance. I’m sure

none of them got anything, maybe some of them got some good pictures, you’re

bound to get a good one eventually if you’ve shot a thousand of them on digital

disks. It was just kind of weird, just too many people shooting photos for no good

reason.

Also, I just wanted more of a natural light.

The flash would bring so much attention and really distort the whole show. I don’t

want to be part of the whole show, I’m just a person there, and when a flash goes

off it’s bringing attention to that exact moment I’m capturing, which I’m happy to

capture, but I don’t need to be awkward and have a flash and getting it in the way

of everyone else. It kind of makes me think, even when I did shoot the last couple of

weeks, how awkward it was and disgusting it was that there were so many fucking

photographers there, sticking their cameras up in the air, not even looking through

the lens trying to get a photo. It was kind of an unfortunate circumstance. I’m sure

none of them got anything, maybe some of them got some good pictures, you’re

bound to get a good one eventually if you’ve shot a thousand of them on digital

disks. It was just kind of weird, just too many people shooting photos for no good

reason.

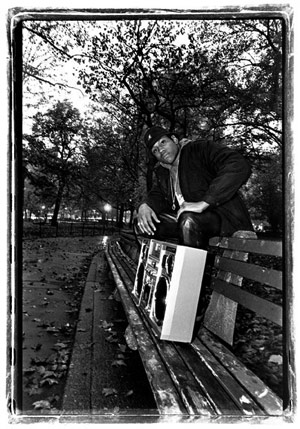

GF: Well, I see it more as fine art. I mean, I am documenting the moment, but there are many other people doing it at the same time. Or several others, and sometimes now it’s many, now it’s insane, but I think the difference is that I’m trying to tell the story of the whole night within 1/60th of a second or 1/500th of a second, and capture some energy, some intensity, some integrity, some character, composition like no one else. I think that’s what separates me; I’m not just there fucking shooting like an idiot, trying to document the moment, not at all, and I never have been. What I shoot has always been a big part of my life—I’m not a voyeur. I’m shooting things that mean something to me, that mean a lot to me. I’m not doing it on assignment, I’m doing it because it’s what I do, it’s what inspires me, that’s why I do it.

GF: Well, I wouldn’t say it’s my story, but I would say what you said after that. It’s how I’m experiencing it, and how I’m, for lack of a better term, idealizing the moment I’m in, in a way that I see it and in a way that I can also tell that story to other people so they can appreciate it, whether they’re a part of the hardcore element that I might be a part of, or not. I always strove to be able to excite the hardcore enthusiast, myself included, number one, but also…you really go to the next level when you make it beautiful or interesting or capture character in a way that anyone, even if they’re not associated with what you’re shooting in any way, can grasp it and feel it and, all of a sudden, are drawn into it because they see that character, that emotion, or intensity, or beauty in it. That’s what I strive to do, because I am trying to inspire other people and not just preach to the converted.

GF: Well, absolutely. I’ve always been very politically motivated. It got more so during the punk rock era, at the end of high school and beginning to go to college, I was becoming more and more educated, not only from school but from the punks around me, people like Jello Biafra and that ilk. I’ve always been politically aware, since I was a little kid, growing up when Vietnam was going on, and remembering the presidential election when it was McGovern vs. Nixon; I would have McGovern written on my clothes and a peace sign out the back window of the parents’ car. I’ve always had a political conscience, but it was certainly brought to another level once punk rock came into my psyche. At the same time, it’s something that always motivated me to take the pictures that I did. Why else would I want to share these moments and inspire people to become rebels? It’s because of my political aspirations, or inspiration, that I want to change things and I want things to be better for everybody.

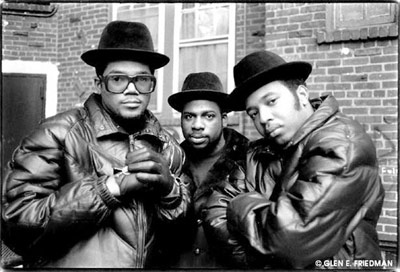

GF: Absolutely, in the beginning. But it was also so dynamic. The politics of hip

hop and the dynamic of the music were totally exciting. I didn’t like punk rock just

for the words; punk rock, the music itself, was incredible to me. There were [also]

many bands that I’d probably prefer that they not make music, that they just write

books.  I could think of some right now, I’d rather not say their names, who had

great politically motivated lyrics but their fucking music sucks. The thing about

hip hop was, at the time when I started getting into it heavy, it was around the

same time that punk rock was becoming very generic. There were a dime-a-dozen

bands trying to be Minor Threat or Suicidal, although no one could really mimic

Black Flag too well—no one could really mimic any of those bands too well, but

they just seemed to be becoming kind of generic. But then came hip hop with this

totally unique, dynamic sound; people scratching records and stuff like that. I just

thought it was kind of incredible. It was just the right music at the right time; it was

black kids’ version of punk rock, in a way. And it was political in the beginning, it

wasn’t so much later on, but I was always attracted to the more political aspects

of it. That’s why I was immediately drawn to Public Enemy and I knew way before

the first album was ready that I would be the one to shoot that cover and any one

afterwards.

I could think of some right now, I’d rather not say their names, who had

great politically motivated lyrics but their fucking music sucks. The thing about

hip hop was, at the time when I started getting into it heavy, it was around the

same time that punk rock was becoming very generic. There were a dime-a-dozen

bands trying to be Minor Threat or Suicidal, although no one could really mimic

Black Flag too well—no one could really mimic any of those bands too well, but

they just seemed to be becoming kind of generic. But then came hip hop with this

totally unique, dynamic sound; people scratching records and stuff like that. I just

thought it was kind of incredible. It was just the right music at the right time; it was

black kids’ version of punk rock, in a way. And it was political in the beginning, it

wasn’t so much later on, but I was always attracted to the more political aspects

of it. That’s why I was immediately drawn to Public Enemy and I knew way before

the first album was ready that I would be the one to shoot that cover and any one

afterwards.

GF: Well, I’d have to say I was definitely born at the right time, but there were millions of other people that were born at the same time as I was. But I made it my business to be there. But I did happen to grow up in West Los Angeles when skateboarding was about to blow up for the second time in the 70s, and yeah, I was in the right place at the right time, but I was motivated by much more. There were other people there who didn’t get those shots that I got, and that goes for punk rock and for hip hop as well.

Being in Los Angeles and having my father living in the New York area, I

traveled back and forth a lot between my parents, so I was able to experience these

different scenes and feel at home in both of them. I made friends in Washington, DC

as well and drove down there. Plenty of people were in these same places at the

same times. And in hip hop not too many people were shooting photographs, but

those who did tried to make it something it wasn’t; people took hip hop into the

studio. Just from my punk rock roots, it was pretty obvious that I would just want to

keep it right in the neighborhood where it was going on.  It had such a vibrant culture

of its own, why would you want to make it bland and put it in a white studio? So,

right place at the right time? I made myself be in some particularly interesting places

at particular times because that’s what was going on and that’s what was inspiring

me.

It had such a vibrant culture

of its own, why would you want to make it bland and put it in a white studio? So,

right place at the right time? I made myself be in some particularly interesting places

at particular times because that’s what was going on and that’s what was inspiring

me.

GF: You keep using that word “document” over and over again…I’m inspired by these people, and I want more people to be inspired by them. I want to take the pictures that are going to kick them in the face and wake them up and inspire them. And I’m gonna do it in a way that I think will do it even more than what anyone else has shown them. You can see something, but if you take it and look at it in a particular way it might inspire people even further, [but] if you’re just some shit- ass photographer taking a snapshot at a show and you get a photo that happens to document the moment, that’s not necessarily going to inspire someone. But I’m being inspired by these people, so I am taking it upon myself to make it so great that it’ll hopefully inspire other people as well; not just those that are there, or not just me, but it really is all about that—it is about spreading inspiration and taking it seriously, and trying to pay back those that are giving so much to me.

for

composition, nevertheless often say much more about a time, a zeitgeist, than about

aesthetics. Then, finally, there are photos like the one of Ian Svenonius and the Make

Up, posed in their fancy clothes up against a graffiti-covered wall, photos that fall

squarely in the realm of glossy publicity shots. Still, they’re composed nicely. There,

I’ve said my peace. —Andreas)

for

composition, nevertheless often say much more about a time, a zeitgeist, than about

aesthetics. Then, finally, there are photos like the one of Ian Svenonius and the Make

Up, posed in their fancy clothes up against a graffiti-covered wall, photos that fall

squarely in the realm of glossy publicity shots. Still, they’re composed nicely. There,

I’ve said my peace. —Andreas)GF: Well, I think I’ve explained that already but I’ll tell you again: it’s that I have an eye for it. Not only do I have the timing to get that precise moment that many people don’t always seem to get, but I care about composition, I care about lighting, I care about character, I care about intensity. That’s what I think tells people and speaks to other people, and so people even outside of what we’re dealing with can appreciate it. If you have a photograph that has character in it, or has intensity in it and is composed well, I think almost anyone can appreciate it. I don’t think you need to know who’s in the picture at that exact moment that you look at it to appreciate it, if all those other elements are in there. Anyone who has any interest in even looking at a photo can appreciate that. Does that make sense to you?

------------------------------

There’s a lot more. Seriously, like another 25 minutes, during which we talked about Glen’s other work unrelated to his current show. At times Glen got up on a soap box, which he is, I think, more or less entitled to, and I think largely that it’s worth having it up on the site. I’ll get around to transcribing it sometime this week, but for now let’s leave it at this.

For what it’s worth, I’d encourage you guys to go see the show. See the work because, fuck it, it is important. Maybe Glen’s an idealist from a bygone era, but don’t we need more idealists right now? Maybe other photographers aren’t as talented, lucky, insightful, and well-intentioned as he is (I tend to think he sounds pretty crotchety when he gets going on one of those rants), but Glen Friedman’s photos should speak for themselves by now. Who cares if he’s bitter or angry? Well, actually scratch that. It’s good that he’s angry. I, for one, would like to see some more anger. Bitterness, though, not so much.

But still, come on, people, let’s make with the anger and the inspiration and the doing of things.

In Part 2 Glen talks about photographing clouds and berates the fuck out of anyone who’s shit-talked Shepard Fairey.

Words and interview by Andreas Trolf

-----------------------------------------------

Glen Friedman Interview—part 2

Interview by Andreas Trolf

I feel compelled to offer a brief comment regarding the first part of this interview/article, which appeared last week prior to the opening of Glen Friedman’s show at 941 Geary, seeing as how both Glen himself as well as some readers seemed so offended by my opinions.

To begin, I have no interest at all in presenting a fluff piece or a press release for anyone, whether that person is a famous and talented photographer or not. If you care to read a glowing piece of fluff devoid of backbone or opinion, I’d suggest reading the SF Weekly’s recent article on Friedman. What I’ve done, I hope to the best of my ability, is present, in conjunction with Friedman’s answers and opinions, my own opinions of his work and philosophy. Is it impartial? Of course not, but as I wrote previously we are all biased in our perspectives. This is opinion, and if it should offend you or differ from your own opinion, you will, I’m afraid, have to learn to live with it. A difference of opinion is one thing, and it is, I believe, inextricable from any conversation, but if it offends you that I have an opinion at all (and that I’m unabashed about sharing it), then I’ll simply quote to you the title of one of Friedman’s (excellent) books: Fuck You Too.

Anyhow, moving on, insulting twitters aside, here is the conclusion to the interview, peppered with my opinions and observations:

GF: Yeah, it has nothing to do with the show that we’re dealing with at the moment, but I’m happy to talk about it.

GF: That’s cool. To talk about Recognize, the beginning of that really starts with The Idealist. In The Idealist book I tried showing people what my aesthetic was, just so they’d understand. And also, for me to just release it, ‘cause I had what I thought were beautiful photos; and after having these two successful books, Fuck You Heroes and Fuck You Too, out there, I thought that it would be really cool to just show the other side of my work that really is all inspired in similar ways, [by] politics and aesthetic, beauty and integrity. But I also wanted people to see that it isn’t just a documentarian, it’s an artist doing this work. And as an artist, it’s nice to be able to share your work and inspire people. I also wanted people to realize that you don’t just take pictures of one thing. A good photographer who’s really an artist can take good pictures of almost anything. I wanted to explain to people, particularly to younger people, that

You understand? And although those are parts of my life, although those things run through my veins, it’s not all that’s in my blood. For people to be able to see that and relate to that, it might bring them in further into what I’m trying to express in my work. And also to show people how to take good photographs; what it is that this person who they’ve looked up to or they’ve seen these photographs [by] that have inspired them, of someone getting a frontside air for the first time, or screaming with a microphone right in my face, or giving me the hardest look on the street corner, also could shoot a picture of anything else and make it look interesting and exciting, or creative in a way that pleases the eye, to say the least.

And I thought that doing The Idealist book would really teach people to take better photographs. And it did in some degree. All of a sudden I did see more kids, in their portfolios, showing more different kinds of work. And I thought that was cool, not to be so specialized in one specific area, but just to have a vision that you could share, I thought was really important, to get your unique stamp on that. But it kind of fell short in some ways, people just said, “Oh, that’s just Glen’s art book…” and they didn’t really get that part of the message. So, come the new millennium, I was so fucking frustrated with the shitty photography that’s out there and so inspired by the beauty I always noticed when I’d been flying, crisscrossing around the globe, either for my shows or just to visit family or whatever, by the clouds that I would see out the windows of the planes. And so I started taking pictures of them; it was too magnificent to not start shooting, I just had to do it, and all of a sudden I get into shooting pictures of clouds and I’m realizing that this is more exciting and challenging than almost anything I’ve ever shot—in some way, not in all ways. And when you consider that I’m in an airplane, in the back of the plane, in coach, looking out a window with a 35mm camera, I have no control in any way over what’s going on. I can’t tell the pilot to circle around, I can’t tell him to slow down. All I know is that I’m going to end up somewhere else, but in between I can’t tell the clouds to stand still, I can’t tell them to do it again, I can’t control it in any way whatsoever. Not only that, it’s gone within a fraction of a second. And so I wanted to show people that this is kind of like a photography 1 class. “This is it, you’re going to learn to compose pictures with something that you have no control over.” I just thought it was an amazing concept.

Besides being absolutely beautiful and recognizing the beautiful nature that’s around us at all times, I want people to recognize what it is to take a good photograph. Let’s start at the base: an absolutely universal subject, clouds. Every single human has seen a cloud; not every human has seen the ocean, not every human has seen a mountaintop, not every human has seen a tall building, except for maybe in a movie, every single human has seen a cloud. Absolutely universal, can we agree on that?

GF: So, let me take this absolutely universal thing and make it into art, as I see it. Not only will I be doing that, but I’ll be doing it with a subject that, as I said before, I have no control over whatsoever. I wait for it to happen, I’m looking through my eyes, looking through the lens, and waiting for that exact moment and composing pictures on the fly. No pun intended, quite literally composing a perfect image within the camera frame and make art out of it and make it beautiful and make it so someone can appreciate it who’s not there with me.

GF: Andreas, it’s even less predictable, it’s even less predictable. Because you kind of know the songs and kind of know when they’re going to have their peak energy, I know nothing with the clouds. And not only that, with the timing and with them going by and having to compose them on the fly like that, much like I got credit for, all of my career, as being part of skateboarding, being part of the music communities that I was in, being in there and getting shots like no one else can because I have relationships with the artists, friendships, and I have respect for them, they have respect for me... I’m not gonna shoot like Stieglitz, one of the only other collections of cloud photographs that I could find in history—I wanted to see if it was done before—it was Alfred Stieglitz, the famous photographer, and all of his photos were taken from the ground looking up.

I wanted to be in the clouds, I wanted to show people what it looked like up in there, and that’s why 90% of the photographs in the book are all taken from airplanes. So I could be in there like a bird, well, most birds don’t even fly that high, actually, but like I’m one of the clouds myself. Like I’m getting a unique vision, like even the photo on the cover, I felt like it was almost like you’re sitting in heaven. Not that I believe in any religious heaven, just what people think of as heavenly. That’s what I see on the cover; it’s like a lounge chair or something. Just a place to sit down and relax. You’re in there, you’re in the moment. You’re a part of the clouds, you’re within the clouds, and you don’t see anything else other than the clouds. You don’t see the earth at all in any of my photos, you do see some ocean water in, I think, two or three shots in the whole collection, but otherwise you don’t see any remnants of humans at all in the book. No traces of mankind in the images.

So again, it’s about bringing it back to the base, and trying to show people with such a simple subject, you know, I was hoping that people would be able to see it and take from it how to compose a beautiful image, how to really take photographs and think about them. Too many people take photographs, even well paid, for lack of a better term professionals, I mean, they just fucking just snap shoot. They don’t fucking think, they just shoot pictures and that’s it, it’s done, and they get paid. All these magazines, the most these art directors want is to fill space in between advertising; they’re not inspired by shit. They’re just filling space to fucking make money or to sell a product, and I’m just fucking sick of that. And I might not be so sick of it if they did it with some quality, but they don’t even fucking care, they have no respect for the art form at all. They just fucking shoot pictures, these fucking snap shooters, and there’s a place for that, but don’t fucking call it art and don’t put it in magazines. You know? Shoot that for your fucking home and put it in your own shitty ass photo album, don’t make me look at your crap. That’s what I feel about most of the photography I see out there—it’s pathetic, man. Do something. There’s so many pretenders…there’s people out there with assistants, shooting pictures, and they don’t know what the fuck they’re doing as an artist, they’re just fucking shooting. It’s The Emperor’s New Clothes, man, some fucking art director said, “Oh, you got it... we like your look, it’s raw, it’s dirty, it’s sexy...”

You’re just trying to tell people it’s something that it’s not because you’re lazy or you don’t want to pay someone what it really costs to get a good photographer, or you can’t even find someone…whose pictures will tell the story, not your graphic design on the page [that’s] taking away from the image. You understand what I’m saying? Did you appreciate the little mini-rant?

GF: If I was a little more candid, I’d mention names. All you have to do is read a couple of my old interviews and you’ll find the names, I’m just sick of fucking giving them free publicity when they’re fucking worthless pieces of shit. Then again, I take that back, they might not be worthless pieces of shit, they might be nice to their families, and they provide for people, that doesn’t make you worthless but it is worthless as far as an artist is concerned. Because you really water down the field, you know? There are people out there who are really creating, and there are some great people out there doing work, and great work is being done, but with all the shit getting the attention, it just waters it all down, man, and you see this shit at galleries and, you know, respected places, and they’re not respected anymore after I see that shit in there.

When I was a kid, I grew up on Sports Illustrated and National Geographic and Surfer Magazine, man, and there was a fuckin’ lot of integrity in those magazines. They had some beautiful images. And I learned from that. Back when I got my first picture published, it wasn’t just anyone who got in a magazine, it was a real fuckin’ big deal. And for a 14-year old, I fucking lost my mind I was so excited. I was so stoked, I couldn’t even believe it. It was a big deal and there weren’t that many magazines back then, and then I got a check on top of it?! God damn, it was great!

GF: Yeah, it was pretty funny. It was pretty awesome. But, you know, the Recognize book is kind of like, “Recognize good photography, recognize art, recognize the beauty that’s always around you, but recognize that, this is the way, at least I’m thinking, that this is the way you should be looking at photographs.” This is a way to look at the world, but it’s really... it’s totally influenced by renaissance artists, it’s made to make you look at stuff and to remember that it’s art. You know, you could reinvent it, you could be a pop artist or do all this other crap, but, come on, man.

And, that said, bringing it to the next level for this particular show, and our collaborations, the guy is articulate—he’s a craftsman, he is a real artist—fuck all those haters.

I don’t give a shit what they say. I’ve seen a lot more than most of them, and you know what? Fucking Shepard is good at what he does, and just because he got fucking caught out there with this Obama shit, hey man, that was his political belief. He fucking did a lot more than any other motherfucker we know in this world with his art, whether you agree with what he did or not, he did it and fuck that photo! That photo was worthless! It was a dime a dozen, bullshit press photo and even the photographer who took it knows it. There was no fucking art involved; Shepard Fairey made that image something very important with his talent—not just fucking Photoshop—he did something, and he deserves credit for that, for better or for worse, depending on your political beliefs. But either way, it was inspiring. I thought it was incredible, and Shepard has a way of doing that with images, and me and him have worked together on several images that were inspiring to him that were already iconic images but he wanted to do his graphic representation of them. Or I thought it would be nice to see his graphic representation of my work, and expose it to more people and inspire more people, and it’s been great. It’s been totally great, man.

And again, I wouldn’t do it with any fucking idiot, I’m doing it with him (Shepard Fairey) because he’s fucking smart and he knows what he’s talking about, and Shepard has a great understanding of my work. He’s grown up with my work, he’s been inspired by my work, and that’s great. Who else would you want to work with, other than someone who has been inspired by and understands what the fuck you do? Know what I’m saying?

and so what if he’s not super radical in everyday life? I don’t need to defend him, the guy does well. He does a lot better than I do, business-wise, but that’s his decision. Okay, at least he’s trying to do something. Too many people just fucking don’t do shit; they just talk. He’s really doing something, and he’s done something, he doesn’t need to prove another motherfucking thing to anybody, as far as I’m concerned, you know what I’m saying, after that fucking poster. He doesn’t need to prove a thing. But he’s an artist, he’ll continue to do what he wants to do, and he’ll continue making his political statements, and I respect what he does.

GF: Well, some people won’t because they say it’s derivative. Because he’s just stealing bits and pieces of other people’s stuff, but that’s not quite fair either.

GF: Well, the show is a best of from a bunch of my books. It’s photos that have inspired people for three decades, and hopefully will continue to. And I think that they do... they just continually inspire people, and that’s what’s exciting about it to me. If people have all my books and they know my work, then there really isn’t much of a need to come see the show. But it is fun sometimes to see the prints up on the walls and go through them with your friends and look at them, but the books tell the story damn well, too, and they look really good in the books.

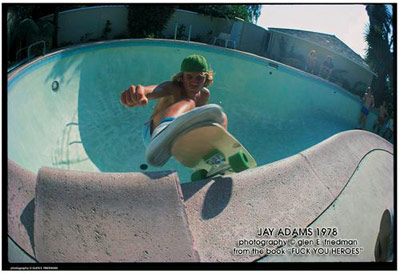

But, as far as the show is concerned, I think it’s more important to talk about our ideals, and why we do it, and why we continue to do it. I don’t do it as much as I used to, but I’m not inspired as much as I used to [be], you know? But I shot some stuff last month! I shot a bunch of music stuff. And since it’s San Francisco, I added a couple pictures of Jello Biafra for good measure, and a shot of Rick Blackhart that’s never been published anywhere. A similar shot was published, since you’re a skater, in Skateboarder in 1978 at the very first pool series, the Hester Series contest they had. That was in Newark, California, which isn’t far from San Francisco, and they were using a hand-poured prototype for Independent [trucks]. So, the first Independent trucks ever ridden in a pool were being used by Rick Blackhart that day. He got second place, but he won the contest as far as everyone else was concerned, or as far as he was concerned. And I got a photo of him on those first Indys just fucking tearing the shit out of that coping with some good style.

---------------------------------

So there it is, folks. I’ve heard it said that nostalgia is history with a sigh, but I’m pretty sure that nostalgia can also include resentment. And I know for damn sure, based on personal experience, that resentment and bitterness wouldn’t be nearly as painful were it not for the wistful nostalgia that drives them. For better or worse. But I still prefer to take a page from Glen’s book, and that is for us all to try, with the best parts of ourselves, to remain idealists.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|